II

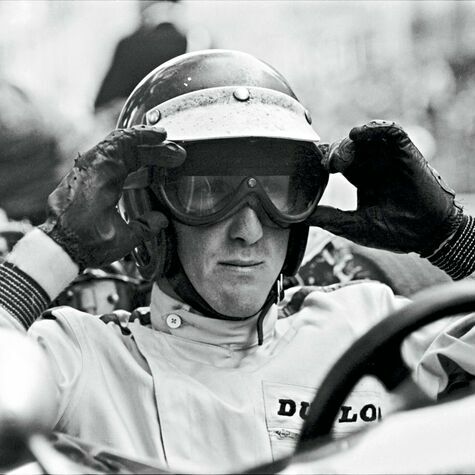

One thing is certain: time is an outgoing prop that cannot be retrieved. We spend just around four thousand weeks here on earth, half of them asleep or in a kind of twilight of consciousness. What remains doesn’t sound like a long, fulfilling life, but more like a short vacation. Four Thousand Weeks is also the title of a very popular bit of reading by Oliver Burkeman, who harshly criticizes the concept of time management. All in all, however, if you google “time-use researchers”, they are a vanishing minority in comparison to watchmakers. Google delivers about four thousand hits for “watchmaker” to every one “time-use researcher”. Watchmakers are busy creating devices to measure time (which is an illusion), devices that can be ugly or beautiful, small or large, with arrows or with numbers. While time-use researchers argue about the right way to use time, watchmakers make us realize how fast it passes by.

Watchmakers (and clockmakers) want to discipline us, they remind us what to do and when to do it, but their time is constantly running in circles and could come to a halt at any second. Time is a constant threat, it is perpetually “not quite”, “around about” or “shortly before”, and the hands, arrows and numbers have a menacing quality, as if the watchmakers were carrying a ticking time bomb that could go off at any moment. The hands permanently pull us toward tomorrow; we resist, having not really savored yesterday yet, but before we know it, every morning turns into yesterday and we, impaled on the pointer, keep turning with the watch.